You know that sinking feeling when you upload a video, your database happily stores the metadata, but then your job queue decides to take a coffee break? Now you've got a video record sitting there like "hey, when am I getting processed?" while your queue is completely oblivious.

This is the classic distributed systems nightmare: you need two things to happen together (store data + queue job), but they live in different worlds and sometimes one succeeds while the other fails.

I ran into this exact problem building a video transcoding system. Users upload videos, I store the metadata in Postgres, then I need to queue a transcoding job in Redis. Simple, right? Until Redis decides to have a moment and suddenly I've got videos in my database that will never get processed.

The transactional outbox pattern saved my sanity here, and honestly, it's one of those patterns that feels obvious once you see it but isn't immediately intuitive.

The problem: when two systems need to agree but don't talk

Let's say you're building something where you need to:

- Store some data in your database

- Publish an event or job to a queue/message broker

The naive approach looks like this:

// This is asking for trouble

async function uploadVideo(videoData) {

// Step 1: Save to database

const video = await db.insert(videos).values(videoData);

// Step 2: Queue the job

await videoQueue.add('transcode', { videoId: video.id });

return video;

}What could go wrong? Well, everything:

- Database succeeds, queue fails → orphaned video records

- Database fails, queue succeeds → jobs processing non-existent videos

- Network hiccup between the two → who knows what state you're in

You can't wrap this in a database transaction because the queue lives outside your database. You're basically crossing your fingers and hoping both systems behave.

Enter the outbox: your reliability safety net

The outbox pattern is beautifully simple: instead of directly publishing to external systems, you write everything to your database in a single transaction. Then you have a separate process that reads from this "outbox" table and publishes the events.

Think of it like leaving notes for your future self. You write down "hey, remember to send this job to the queue" in the same transaction as your main data. Later, a background worker reads these notes and actually does the work.

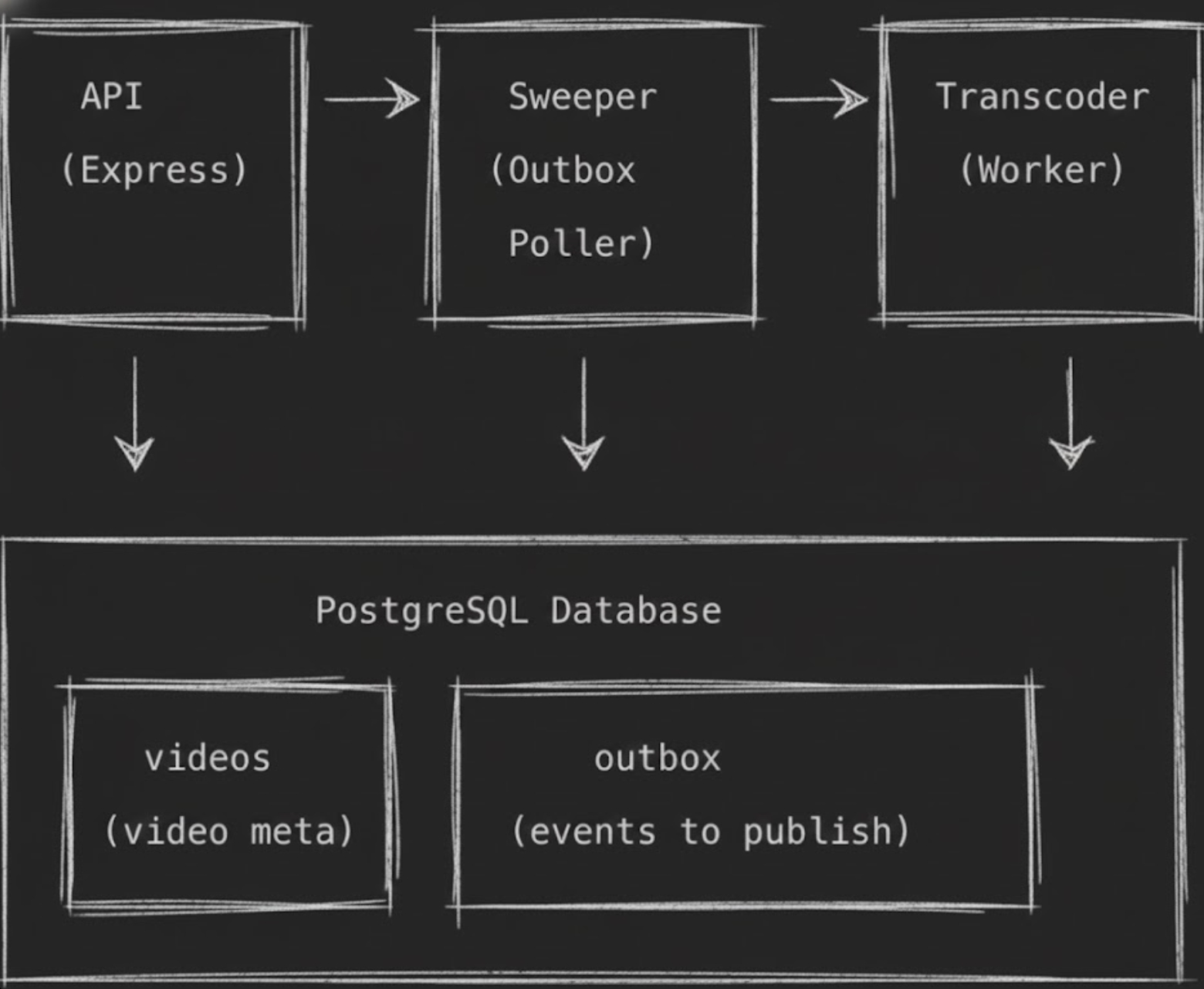

Here's how I structured it in my video transcoding system:

Two tables, one transaction. The magic happens in that atomic write.

Step 1: The upload handler - write everything atomically

When a video gets uploaded, I store both the video metadata and an outbox event in the same database transaction:

async function handleVideoUpload(videoFile) {

const result = await db.transaction(async (tx) => {

// 1. Insert video metadata

const [video] = await tx.insert(videos).values({

filename: videoFile.name,

size: videoFile.size,

status: 'uploaded',

uploadedAt: new Date()

});

// 2. Insert outbox event (ATOMICALLY in same transaction)

await tx.insert(outbox).values({

uploadId: video.uploadId,

eventType: 'video.uploaded',

payload: { videoId: video.id, filename: video.filename },

status: 'pending',

createdAt: new Date()

});

return video;

});

return result;

}Both inserts happen together or not at all. If my database is happy, I know both records are there. If something fails, nothing gets written. No more orphaned records.

Step 2: The sweeper - your reliable background worker

Now I need something to actually read from the outbox and publish to the queue. Enter the "sweeper" - a background service that polls the outbox table and processes pending events:

async function processOutbox() {

await db.transaction(async (tx) => {

// 1. Lock and fetch pending rows (prevents double-processing)

const pendingEvents = await tx

.select()

.from(outbox)

.where(eq(outbox.status, 'pending'))

.limit(10)

.forUpdate()

.skipLocked(); // This is the magic sauce

if (pendingEvents.length === 0) return;

// 2. Mark as processing

await tx.update(outbox)

.set({ status: 'processing' })

.where(inArray(outbox.id, pendingEvents.map(e => e.id)));

// 3. Publish to queue

const jobs = await Promise.all(

pendingEvents.map(event =>

videoQueue.add('transcode', event.payload)

)

);

// 4. Update with job IDs and mark as sent

for (let i = 0; i < pendingEvents.length; i++) {

await tx.update(outbox)

.set({

status: 'sent',

jobId: jobs[i].id,

processedAt: new Date()

})

.where(eq(outbox.id, pendingEvents[i].id));

}

});

}

// Run this every few seconds

setInterval(processOutbox, 2000);The FOR UPDATE SKIP LOCKED part is crucial - it lets multiple sweeper instances run without stepping on each other's toes. Each sweeper grabs a batch of rows, locks them, and processes them independently.

Step 3: The transcoder does its thing

The transcoder worker just consumes jobs from the queue like normal:

const worker = createVideoWorker(async (job) => {

const { videoId } = job.data;

// 1. Download video from S3

// 2. Transcode to HLS (360p, 480p, 720p, 1080p)

// 3. Upload HLS files back to S3

// 4. Update video status to 'completed'

await db.update(videos)

.set({ status: 'completed' })

.where(eq(videos.id, videoId));

});Clean separation of concerns. The transcoder doesn't need to know about outbox patterns or reliability concerns.

Why this actually works (and why I love it)

Consistency: Your database and queue can never get out of sync because the database is the source of truth.

Reliability: If your queue is down, events just pile up in the outbox. When it comes back, the sweeper catches up.

Scalability: You can run multiple sweepers. The SKIP LOCKED ensures they don't conflict.

Observability: Your outbox table is an audit trail. You can see exactly what events were published when.

Retry safety: If a job fails, you can reprocess it from the outbox without duplicating database writes.

The trade-offs (because nothing is free)

Eventual consistency: There's a delay between writing to the outbox and publishing the event. Usually seconds, but still not immediate.

Extra complexity: You need that sweeper service running. More moving parts.

Database overhead: Every business operation writes to two tables instead of one.

Cleanup: You'll want to periodically clean up old outbox records (or archive them).

For my video transcoding system, these trade-offs are totally worth it. Videos don't need to start processing instantly - a few seconds delay is fine. But losing a video upload because of a queue hiccup? That's not acceptable.

When to use this pattern

The outbox pattern shines when you need:

- Reliable event publishing alongside database writes

- At-least-once delivery guarantees

- Audit trails of what events were published

- The ability to replay events from a specific point in time

It's overkill for simple CRUD apps, but once you're dealing with distributed systems, background jobs, or event-driven architectures, it becomes incredibly valuable.

I've used variations of this in inventory management (stock updates + reorder alerts), and now video processing. It's one of those patterns that, once you understand it, you start seeing use cases everywhere.

The best part? It's not some fancy new tech just good old-fashioned database transactions doing what they do best, keeping related data consistent.